Lawfare Daily: Susan Landau and Alan Rozenshtein Debate End-to-End Encryption (Again!)

Published by The Lawfare Institute

in Cooperation With

In response to the compromise of telecommunication companies by the Chinese hacker group Salt Typhoon, senior officials from the FBI and CISA recommended that American citizens use encrypted messaging apps to minimize the chances of their communications being intercepted. This marks a departure in law enforcement’s position on the use of encrypted communications.

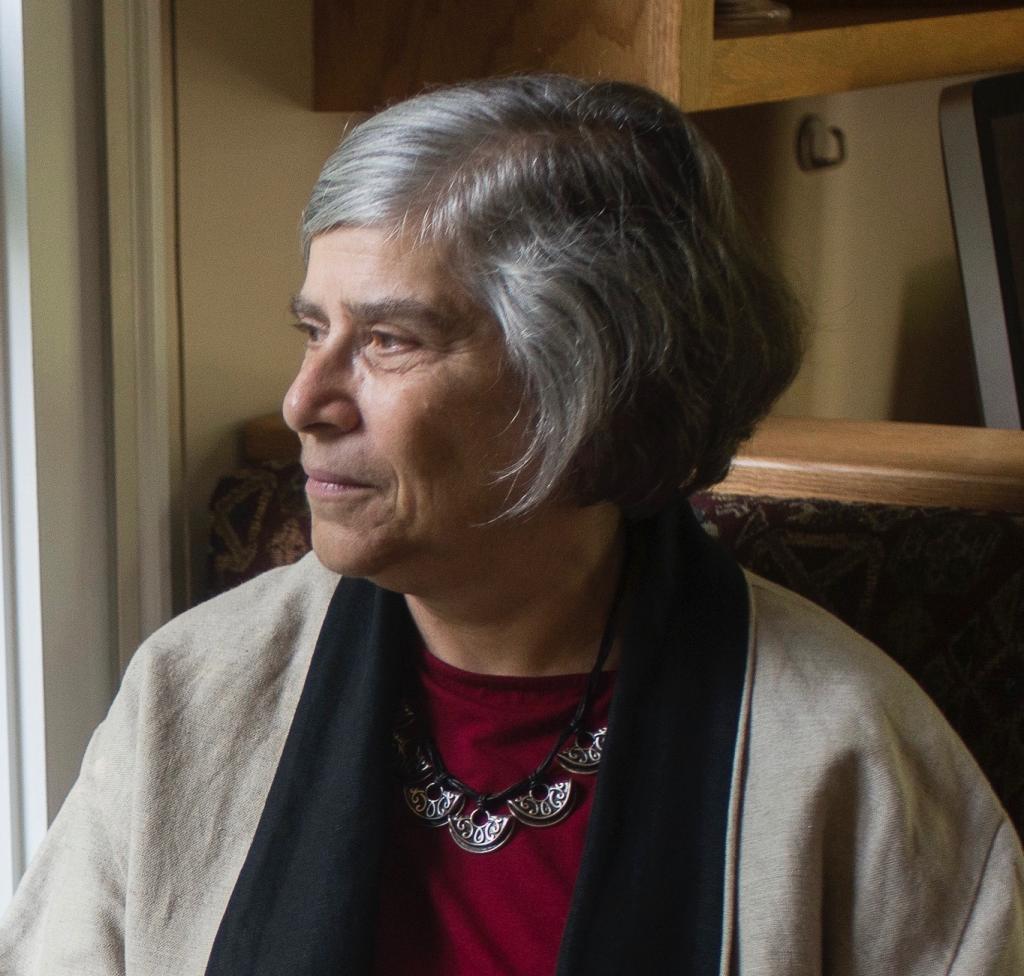

Susan Landau, Professor of Cyber Security and Policy in Computer Science at Tufts University, and Alan Rozenshtein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Minnesota Law School and Research Director and Senior Editor at Lawfare, sat down with Lawfare Senior Editor Eugenia Lostri to talk about what the recent FBI recommendation in favor of the use of encrypted messaging apps means for the “Going Dark” debate.

To receive ad-free podcasts, become a Lawfare Material Supporter at www.patreon.com/lawfare. You can also support Lawfare by making a one-time donation at https://givebutter.com/lawfare-institute.

Click the button below to view a transcript of this podcast. Please note that the transcript was auto-generated and may contain errors.

Transcript

[Intro]

Susan Landau: My understanding of responsibly managed encryption is it's code word for don't use end-to-end encryption because we can't break in. Store the keys with somebody else, like the phone provider or a different third party, and do I believe that's responsibly managed? Well, CALEA was responsibly managed also, right? No, I mean, the best way to secure your communications is end-to-end encryption.

Eugenia Lostri: It's the Lawfare Podcast. I'm Eugenia Lostri, senior editor at Lawfare, with Susan Landau, professor of cybersecurity and policy and computer science at Tufts University, and Alan Rozenshtein, associate professor of law at the University of Minnesota Law School and research director and senior editor at Lawfare.

Alan Rozenshtein: A lot of it was the quiet that we saw, right, which showed to me that the lawful hacking solution that I was skeptical of, was more robust than I originally thought. And then plus seeing this CALEA disaster just as a very vibrant reminder of the kind of worst-case scenario.

Eugenia Lostri: Today, we're talking about the recent FBI recommendation for the use of encrypted messaging apps and what that means for the “going dark” debate.

[Main Podcast]

So I actually think that the best way to start the conversation is if we can recap the long history of you two talking about encryption and disagreeing about encryption, I think that really sets the stage for what we're about to experience.

Susan Landau: So then the way we could do it is I could say, well, first there was Louis Freeh, then there was Jim Comey, then there was Alan Rozenshtein at a Privacy and Legal Scholars Conference.

But I don't even fully remember the second half of the argument. I remember the first half, which was wicked problem. And we kept saying to you, write the wicked problem paper. Just the wicked problem part. I don't even remember, except that you were wrong. That's the part I remember.

Alan Rozenshtein: And we are all here gathered to celebrate that. Yeah, so, what Susan was referring to is about seven years ago when I was an innocent visiting assistant professor at the University of Minnesota. No tenure track job. Alan

Susan Landau: Alan is never innocent.

Alan Rozenshtein: No, nothing. Yeah that's fair. I wrote–as my what was going to be my job talk to get my tenure track job, which did work in the end, thank God–a paper called Wicked Crypto, in which I tried to sort of analyze the going dark issue and explain all the sides and do the sort of both sides triangulation that I am constantly doing because I can't help myself.

And so I submitted this paper to this privacy law scholars conference, which is one of the kind of premier law conferences about this kind of stuff. And it got accepted, which was very exciting. It was my first, like, big conference, and I go, and you know, a week before I discovered that Susan Landau is going to be my discussant, which fills me with just absolute terror. And of course it's Susan Landau, so the room is packed, right? And I was, like, basically standing alone.

Susan Landau: No, it's Alan Rozenshtein's paper, it's not Susan.

Alan Rozenshtein: Yeah, I'm pretty sure it was, people came for Susan. And so I get there, and the way it works is that the discussant actually presents your paper, so Susan begins, and she says, she presents the paper, and she says, this is very interesting, Alan, I have 17 thoughts.

And I just think, oh my god. So, I recall it being an extremely polite evisceration. But in the end, you know, I, it got me a job. So, I am in the end, however wrong I may have been, I am still pleased. And it is delightful, Susan, to seven years later, come here so we can all celebrate your total. I don't want to say total, we'll get into it, but your pretty conclusive victory in this particular battle.

Susan Landau: So, my memory is that I was not just the only one in the room, there were other people in the room, and my long term colleague, Steven Bellovin, was there, and Steve and I kept saying to Alan look, look, this first half of this paper, this is really good, the wicked problem part is good, just cut the second half, and it took a lot of badgering Alan, but eventually he came around.

Eugenia Lostri: What was the second part?

Alan Rozenshtein: I don't know. It was like some solution or something. I think we were gonna, I don't know. It was pretty milquetoast, but I mean, it was basically, the paper was basically the idea that this encryption problem is a hard problem.

Eugenia Lostri: Revolutionary.

Alan Rozenshtein: Yeah, exactly.

Eugenia Lostri: Yes. Okay, so you guys have been talking about this for at least seven years. But the reason why we're here today talking about it is a few weeks ago, and unfortunately, as a response to the compromise of telecommunication companies by allegedly Chinese hackers, we've had senior officials from the FBI and CISA recommend that American citizens start using encrypted messaging apps to minimize the chances of their communications being intercepted, right?

And this marks a departure for the way that law enforcement has been talking about the use of encryption. They've actually been arguing against it for some time. So, actually, Alan, I am going to turn to you first, just to ask you if you can give us an overview of the going dark argument, right? This is something that most listeners are going to be familiar with, but I think it's an important point just to have up front.

Alan Rozenshtein: So the idea is that since the beginning of widely available, relatively easy to use encryption software, which really starts in the late 80s and 90s, there's a concern from law enforcement that this was going to cause a severe degradation in the ability of law enforcement to do its job, which is to say law enforcement can suspect you, do the investigations, get a warrant, right? Show probable cause, do all of the stuff they're supposed to do.

And then when it comes to actually executing on that warrant, you know, they'll be able to get a physical copy of your hardware, or they'll be able to access your communications, but they're going to be encrypted and that's going to be a real problem for them.

So, you know, starting in and, you know, Susan literally lived through this so, she will perhaps have a more vivid recollection of this than I am.

You know, really starting into the, in the mid nineties, there were these successive waves of what have been called the crypto wars, which is basically this concern over government access to communications. And I should also say, although encryption is sort of the highest profile version of the going dark fight, and it's how it's been fought in the last 10 years, really, the problem is actually not just about encryption, but it's more generally about any time that the police or the law enforcement or the intelligence agencies worry that they're not going to be able to do their jobs because of some technological impediments.

And so again you've had different versions of this fight, right? So you had a version of this fight about encryption in the 1990s. You had a version of this fight and this is most relevant to, you know, what happened a few weeks ago where the move from analog to digital telephony, right, going from actual copper wires that you could, you know, put alligator clips on, in kind of the old school you know, FBI mob movies when you wanted to do a wiretap on someone, to digital switches created a concern that, you know, even if the law enforcement could get a wiretap order, there was like nothing to actually wiretap.

And so this led in the 1990s to the passage of this law called CALEA, which I'm sure Susan will have much more to say about, which forced these telecommunication companies to have an ability to comply fit technologically with wiretaps, right? So that's kind of another version of the going dark concern.

And then most recently you had a going dark kind of another flare up in the early 2010s. There's a famous, I think, speech by then-FBI director, Jim Comey, where he's concerned about this. And this is really because at that time you had the proliferation of smartphones, Android devices, and especially Apple iPhone devices that would provide really secure full disk encryption by default. So, you know, again, even if the cops got the phone. They couldn't get into it because, you know, they would type the password four times incorrectly, and then the phone would be locked forever, and it was very difficult to hack into it.

And this kind of reached a fever pitch. And actually, I was in the Department of Justice at the time, I wasn't directly involved, but I sort of had a front row seat to a lot of these discussions. The San Bernardino iPhone. So this was, I forget the exact date. I think this was 2014, 2015?

Susan Landau: December 2015.

Alan Rozenshtein: Yeah, 2015. There was a shooter goes into, I think, strip mall or an office park in San Bernardino, and kills a lot of people. He is, or is suspected to be a lone wolf terrorist type connected to, I, maybe I think it was ISIS?

In any event, he is shot and killed at the scene of the crime. The FBI get his phone, but they can't get into it because it's one of these late model iPhones. And so they send, they get a judge to order Apple to basically tweak the operating system that's on that phone to make it easier. Apple refuses. Tim Cook ends up on the, you know, front page of Time magazine, basically. And this, I think, is kind of the big, big flashpoint of the latest version of going dark, right?

And my tiny role in this, that this led to my first two law review articles and why I'm a law professor today. So this is sort of close to my heart. Obviously, that's far from the most important part of that story.

But basically, we've been fighting this issue one way or the other. And the kind of steady state that we've settled into, and I think this has been Susan's sort of really big contribution to the debate, is this idea of what's called lawful hacking, where basically, either because it's very hard to create a hack-free technology, and no matter how good Apple is, the FBI is pretty good too and can usually, with enough investment of time and resources, find a way, either itself or by buying off the shelf tools.

And this is actually what happened in the San Bernardino case, Director Comey famously went to Congress and testified that you know, the FBI had spent more than his like annual salary, four times his annual salary or something, on some tool to get into an iPhone, so either because it's just hard for these companies to create perfect hack-proof devices, or because there's kind of a tacit understanding between these companies and the government that these companies can advance the encryption software, but just don't do it so fast and so well that it becomes impossible for the FBI to do its job on at least older model devices.

Either way, there's kind of been a sort of truce slash detente kind of around the lines that I think Susan has advocated for, which kind of satisfies nobody because, you know, the law enforcement can't get into 100 percent of the phones it wants to. And then like the really hardcore cybersecurity people are annoyed that the FBI can get into any phones whatsoever. But this kind of compromise solution has made it such that the law enforcement get into enough phones to do enough of its law enforcement and everything is fine.

Now, the CALEA thing is a separate issue as we'll talk about, but I would say that is a very potted summary of the last 25 years of going dark. But Susan, tell me all the ways that I screwed that up.

Susan Landau: So, oh, lots of ways, lost of ways!

Alan Rozenshtein: Susan's like, I have 17 comments!

Susan Landau: 34 this time!

Alan Rozenshtein: Oh, great, great.

Susan Landau: So the crypto war started back in, actually in the 1970s when people started coming up with ways that two people who had never met could exchange bits over the network, and even if anybody observed their communication when they did so, they were actually able to encrypt their communications.

This was very interesting mathematics. It was done by my co-author, Whitfield Diffie, and his advisor, Marty Hellman, and at first the NSA even thought about trying to prevent the publication of this, but it was fairly easy mathematics, in fact accessible to smart high school students, and it went all over. And the NSA gave up on the idea of trying to prevent publication restrictions, including publication restrictions of academic research in cryptography. There was just that period in the late seventies, early nineties, early eighties, when that was discussed.

In the eighties, there was an attempt by NSA to move the standardization of encryption done by the federal government for non-national security agencies, like, oh, Health and Human Services, and so on. Move it from the National Institute of Standards and Technology to the NSA. That got thwarted, and the Computer Security Act said, no, that belongs in NIST. But, what happened then is there was a technical working group, and the technical working group, which had three people from NSA and three people from NIST, kept blocking certain kinds of public-type algorithms, And in pushing instead algorithms where perhaps they had a backdoor or other things that made it harder to do.

That changed actually in the mid-1990s when the composition of that technical working group included somebody from NSA who actually believed that the U.S. civilian sector should have strong encryption. And that was actually a shift, not just because of that person, but because NSA shifted. As computing became much faster and cheaper, other nations began implementing the system and related systems that made it easy to encrypt, over the networks in ways that NSA found it harder to deal with.

And by the late 1990s, the NSA no longer wanted to use export control, which was its method for controlling the development of, and use of strong forms of encryption in computer and communication technologies that were exported. So why do we care about what's exported? We care about what's used here.

Well, it turns out that if you control what's exported, computer and communication companies don't want to make products with stronger encryption domestically, because it's really hard to say to the Swedes or the Brits or the French or the Nigerians or the South Africans, oh, we're selling you equipment with weak encryption. We sell the same equipment with strong encryption domestically, but don't worry about it. Don't worry about it. It doesn't work.

So, in the late 1990s, both the European Union and the United States shifted their policy on devices with strong encryption. And with very few exceptions, it became possible to export devices, computer and communication devices with strong encryption and those of us in the industry then expected to see, you know, all sorts of devices with strong encryption. This didn't happen for a while and that's where the story gets interesting on the safety and security side.

Because when the iPhone came out, there's this small device and it's worth a lot of money and people sit on the subways playing with it and then somebody's standing right by them as the subway door is about to close and the person grabs the phone, runs off the subway car, and now has a $600 device stolen.

So, very quickly, Apple put in, Find My iPhone, and then Android did the same thing. And then, these thieves figured out, well, the other thing they can do, is if somehow they can break into phones or break into lost phones, they can then get data off of them, and the data they can get off of them allows them to do identity theft.

In fact, there was a Chinese criminal group that actually posted a video, which they would sell on how to break into phones and then do identity theft. So Apple then began encrypting data on the phones. And this led to the noise from the FBI saying that things are going dark. They can't get data off the phones.

What is interesting in this period from 2000 on is you don't hear that same kind of complaint from the NSA. The NSA, which had said to the U.S. government, you know, or to the executive branch, you know, we're willing to back off on the encryption export control issue if we get more funding to break into networks. And so there was a trade off that happened. In the late 90s, and since then, NSA has been very quiet about any issue related to not being able to get into devices. Now, sometimes, of course, they do break into devices. And I do, I have heard from people at the agency that it's gotten a little harder. The best kinds of vulnerabilities have disappeared somewhat because we're better on security.

But the fact is that the NSA saw a very useful trade off in being able to break into networks, but let the American public have the ability to encrypt their communications. So, I would phrase the fight we've been having as a security versus security fight, or a security versus public safety fight.

Alan Rozenshtein: Interesting. So, the NSA got the lawful hacking memo two decades before everyone else, in a sense?

Susan Landau: Oh, yeah. I mean, that's their job, isn't it?

Yeah, and you see it, I mean, you see it in the lack of testimony, at least public testimony. And you also see it in the number of comments that happened from ex-senior officials, not just from NSA, but also from General Communications Headquarters, GCHQ in the UK. Ex-senior heads of the agencies saying, I believe that the public is better served by having access to strong encryption, by which they mean end-to-end encryption communications encrypted between the sender and the receiver.

Eugenia Lostri: So as we kind of hinted at up top, we're talking about this today because of the Salt Typhoon breach of telecommunications companies. So, Susan, what do we know so far about this compromise and how it happened? And in particular, I'm interested in hearing how this connects to CALEA, which Alan mentioned before.

Susan Landau: Sure. So in terms of technical details, the government, the U.S. government has been very closed-mouthed, but what we do know is there appear to be two different kinds of things that happened. So, yes, they got into the telecommunications networks, and this is probably due to the problems, both Signaling System 7, but also with the access between the internet and the telephone switches.

Now, the two kinds of breaches that are highly problematic, one is apparently the, Chinese hackers have gotten into the CALEA databases, which means that they have access to knowing who the U.S. has under surveillance for criminal wiretaps. And that means, of course, not just the Chinese spies that the U.S. government has figured out, but the Russian spies, the North Korean spies, the Iranian spies, and so on. And, of course, that's useful information for the Chinese government to have to trade off with other nations, other adversaries of the United States.

The other thing is by having gotten into pieces of the telecommunications network, and this is a separate thing from, or an apparently separate thing from the CALEA breach, is the ability to get into texts, and texts are communications that, the way people do a phone call is there are two parts to your communication. There's the call data channel. You dial in the phone number, dial, of course, being an old word that most people listening have not actually used, one of those black telephones on their desk where you dial.

But you dial, you press the digits of the number, and that travels over the call data channel. Once your call is connected, then your communication is going over the call communications channel. But if you send a text the text goes over the call data channel, and the call data channel isn't encrypted because it's supposed to tell telephone companies how to connect the call, who's calling whom.

And so, texts sent over the phone wires are not encrypted. Texts sent between an Apple device and Android device aren't encrypted. Many texts aren't encrypted. And so apparently the Chinese have gotten into that part of the network too. That is a separate issue from CALEA.

Eugenia Lostri: So we had both CISA and the FBI recommending, now, the use of encrypted messaging apps, but there were some interesting differences in how they framed this, right?

According to some of the reporting that I saw, CISA was basically like, hey, encryption is your friend: go for it. And the FBI says, and I'm going to quote here, “People looking to further protect their mobile device communications would benefit from considering using a cell phone that automatically receives timely operating system updates, responsibly-managed encryption, and phishing resistance.”

Now, the phrase responsibly-managed encryption raises a few flags, and so I want to hear from both of you, what do you understand responsibly managed encryption to mean? And is it even possible?

Susan Landau: My understanding of responsibly managed encryption is it's code word for don't use end-to-end encryption because we can't break in. Store the keys with somebody else, like the phone provider or a different third party, and do I believe that's responsibly managed? Well, CALEA was responsibly managed also, right? No, I mean, the best way to secure your communications is end-to-end encryption.

And I may even have Alan agreeing with me finally after all these years.

Alan Rozenshtein: Yeah, I mean, so let me, I'm a law professor, so let me make two annoying meta points here. Because I totally, I 100 percent agree with Susan in her reading of what this kind of odd language means. And I also agree with her, and I kind of always have agreed with her, that the best way of securing your information is through end-to-end encryption. I don't think that was ever, really, up to debate.

Let me say two things. First, I think this is just a very interesting example that the government is a they, not an it, right? It contains multitudes, different parts of the government have different priorities. There's nothing wrong with that per se, right? I mean, that's in some sense, right? That's why we have a single president to make the hard calls, right? When the different agencies are in conflict with each other. And it is very natural that CISA would be 100 percent end-to-end encryption all the time, because their goal is cybersecurity. Like, it's not that complicated.

The FBI's goal is more complicated. I want to defend the FBI here a little bit, right? Because it is tricky for them. On the one hand, they need to do offense, right? They need to go and investigate the bad guys. And if the bad guys have information that is encrypted, they have a real problem. Right? They have a real problem on their hands.

And there are people whose job it is at the FBI is to go after the bad guys, and obviously their incentives are therefore to try to do that in the best way that they can. The FBI also, however, has a defensive role. Right? They're trying to help prevent crime. And so, you know, in that perspective, they may rightly, right, understandably say that the best way to prevent crime sort of on net is to have more encrypted communications.

And so you have these two parts of the FBI that are themselves at war with one another and so you end up with these very carefully crafted communications, which, you know, they're in part, they're carefully crafted because it's the actual substance of what the decision maker thinks. In part it's because the decision maker wants to give, you know…oh boy. So that when director Kash Patel—God bless us all—goes in front of Congress six months from now, right., hhas the appropriate, you know, breathing room to say, I want this kind of encryption without that kind of encryption.

And also, and this is getting very bureaucratic, but I was in the bureaucracy at the time, you have a lot of internal stakeholders who are themselves going to be extremely pissed if they can't find their view represented in some way. So that's why you have this like very carefully crafted FBI memo.

Here's the other thing I want to say. I am happy, right, to come on this podcast and, like, congratulate Susan on her win, right? Because like, you know, to be an honest interlocutor in this debate, you have to be receptive to data. You have to be like a good Bayesian updater. And man, CALEA getting hacked? That's rough. That is a bad thing. And that has to make us update our priors, right? Has to make us update our priors as to the very difficult, predictive policy judgments of what should you want. And I am totally happy to say that CALEA, this hack, Susan's commentary on it, Susan's scholarship generally, right, has definitely shifted my priors, right? In a nontrivial way.

But this, and this is kind of the, probably the real point I was trying to make in that article almost a decade ago. The problem never quite goes away entirely, of course, because the trade offs are real. They never go away. The science is constantly evolving on the offensive side and the defensive side. And so I think it's foolish, both as a, kind of practical matter, but even that just as an intellectual matter to ever think that this debate is done with forever, right? I think all that can happen is the parameters of the debate, right, shift. And right now there's no question that they've shifted very much in the side of those who favor look at the end of the day, just encrypt everything. It's just simpler that way. The net result is better.

But you know, right now, that's the vibe because of the CALEA hack, as it should be. Six months from now, if there's another San Bernardino-type shooting, right? The vibe's going to shift right back. Maybe not all the way, but we're just going to kind of keep having this conversation forever because the equilibrium that we have is so fundamentally unstable, right? Because you have these two legitimate interests on both sides. And that's just the other point that I want to make.

Susan Landau: So I would step in here and say that one thing we're not discussing is the availability of all sorts of peripheral information, whether we're talking metadata or all the electronic records and so on, that exist about us in a gazillion different ways. It's something that the NSA makes a huge amount of use of.

And for example, it was particularly useful, that communications metadata was particularly useful under searches post-September 11th when what you were trying to track was a terrorist group organized very much under a corporate-level model. So, communications metadata showed you all sorts of useful things.

FBI has a different job. It has to prove things in a court of law, as opposed to gathering intelligence. But as Alan said, and I very strongly feel, well, Alan said, they have a public safety side. I would say that they have not paid as much attention to the public safety side, as they should have. There were times when the FBI had on its webpages encrypt, and then as they, as the going dark battle heated up, those pages went, that page went dark as it were.

And if you think about the kinds of problems that the U.S. is facing in terms of the amount of data that is being siphoned out of the United States, that would shift the discussion to talking about private sector collection of personal data and so on and so forth, and we only have, you know, 50 minutes for a podcast or 40 minutes for a podcast, not 24 hours.

But in terms of what adversaries are attempting to collect the more we can protect data, the better off the United States’ long-term security. And so, part of the debate is really about short-term solutions of criminal investigations versus long-term security of people within the United States.

Eugenia Lostri: Let me get back to you. You mentioned that your own priors have shifted given CALEA. So, tell us a little bit more about how you've shifted, how you're thinking about it. What are the arguments of the going dark aspect that you represent that you still find relevant or plausible, even with these priors being moved?

Alan Rozenshtein: Yeah, I don't think, to me, the arguments were never the hard part, as it were, I mean, I thought that, look, people made bad arguments, fine, but I'm not interested in the bad arguments, right, I was not interested in entering the sort of culture war around going dark, right? I was interested, and I really didn't have any priors going into that debate, I was not trying to carry water for one side or the other, I was really trying to understand: what were the good arguments? And I think the good arguments were quite well understood. I think they were pretty well understood 30 years ago. I don't think they changed fundamentally, right?

The question is where we are at any given time, how do those arguments stack up? And I think, again, not to get too meta, I think that's true of many policy debates, right? You know, pick your random policy debate, you know, taxes, health insurance, this, that, or the other thing. The arguments, the different sides, the trade-offs, the different mechanics and mechanisms, they're often pretty clear, right? You kind of know what each side has to offer, and then the question is, at any given time in history, right, how does it net out? And that can change over time, right?

So, if I was, you know, let's say, more sympathetic to the going dark side, than a lot of academics and civil society folks were, and I should say, from their perspective, I was very much a law enforcement person, but from law enforcement's perspective, I was a useless squish because I spent a bunch of time criticizing what I thought were some very silly statements made by law enforcement, alright, at the time. So again it all depends on what your reference frame is.

You know, if at that time I was willing to go into the Privacy Law Scholars Conference and say that going dark had a good point, which I still am, because I'm a troll, but that's a different, that's a post-tenure thing. It was because I thought that I was worried about the public interest harms. I was frankly skeptical, in a way that I've become less skeptical of, of the proposal that Susan and her colleagues made, that you could have a relatively stable equilibrium of lawful hacking, whereby you know, if the cops want into a system, they just go and invest into getting to that system, but they don't rely on prebuilt help from that system's architects. I was quite skeptical that that would actually work.

And what's really changed for me, you know, is not so much this hack. I mean, this hack could have always happened. I mean, it's particularly bad the way it happened, but it could always happen. What for me, has changed my priors, at least for the moment, and I want to truly emphasize, for, like, the 17th time, this is all revisable, right, as the world continues, and different threats pop up and stuff like that, is that I hadn't heard a lot about this issue for about five years, that for about five years, it seemed that these companies, you know, Apple in particular, were improving their security with every generation of the iPhone.

And yet the FBI was kind of quiet. And that led me to think that the ecosystem of, you know, third-party hacking tools was sufficiently robust that the FBI, sort of, stopped caring. And that told me something, right? And that's why over time I got more comfortable with the quote unquote anti-going dark side of the equation.

So that's what I would say. It's not so much that the arguments change that much for me. It's more just that, you know, the arguments are always kind of generic. How they net out depends on the facts 0n the ground at any particular moment. And I think that, you know, if people spent less time yelling at each other about the abstract, and more time just looking at, okay, but in this moment, which side seems to be providing the most social utility, I think that's a better way generally to have these kinds of policy arguments.

Susan Landau: So I'm going to add a couple of things to, or comment on a couple of things that Alan just said. One is, long ago during generation 1.5, 2.7 of the crypto wars, Brian Snow, who was technical director at the Information Assurance Directorate, said to me once, he said, you know, the Fourth Amendment gives the government the right to get a warrant to get into a system, but there's nothing that says it needs to be easy.

And that was one thing that FBI kept asking, was that it should be easy. Like Alan, I have, well, in a different way, I have spent the last 30 years thinking, I've dealt with the crypto wars. I wrote a book with Diffie. I wrote a paper on CALEA and VoIP with a lot of people. I wrote a book on CALEA. You know, each time I do this, I think, okay, I'm done. Now I can go work on something else. And each time I get pulled back into the encryption wars.

But I think one reason that it's been kind of quiet the last five years is back in 2019, the Carnegie Endowment pulled together a group of people, including Avril Haines who has been director of Office of National Intelligence, Lisa Monaco, who's in Department of Justice, Jim Baker, who had been general counsel at the FBI during the San Bernardino case, and Chris Inglis, who had been deputy director at NSA. And we all discussed moving the encryption policy debate forward, and one of the points, there were a number of points from that report, which I think is still quite relevant today, but one of them was, you know, if you're going to require some sort of compromise and some sort of law, first, make sure that there's a technology that can satisfy it, and that was a really big point.

And then all of these people shortly after the report ended up in senior positions. The ones that I've mentioned, with the exception of Jim, ended up in senior positions in the government, Jim and Chris didn't, but Lisa Monaco and Avril Haines did, and I think that's part of the reason that we haven't seen so much noise from law enforcement over the last few years. But I agree every time I think that it's time for me to find another research topic and move away from encryption, I only get to do it for a couple of years, and then I get drawn back.

Alan Rozenshtein: I'd love to ask Susan a quick question. And sorry, I'm not trying to steal the podcast from you, but when I have Susan Landau in front of me, I just like, like to ask her questions.

Eugenia Lostri: I know you can't help yourself.

Alan Rozenshtein: I cannot help myself. So I want to, I'm curious with this last thing you said because I have heard this argument made and I totally get it.vIt did make sense, which is look, you can't demand something that doesn't exist. And you know, this was in the context. I remember, I forget who, maybe it was Jim Comey, maybe it was Chris Wray, I don't remember who it was, went to Congress. And he said, you know, I'm very unconvinced when the tech companies tell me that they can't do this. They're very smart. You know, like they built an iPhone. They can do this stuff.

Susan Landau: Jim Comey.

Alan Rozenshtein: Ah, it was Jim Comey, okay. And I remember like the joke, which was kind of a funny joke, was like, that's the equivalent of going to NASA and being like, you guys are amazing, you put a man on the Moon. Can you put a man on the Sun, please, right? She's like, you misunderstand.

Susan Landau: That's my friend, Matt Blaze, who came up with that.

Alan Rozenshtein: Yeah, that’s Matt Blaze. That's a good quote. Like that is a good snappy quote. And on the one hand, it's true. On the other hand, it actually is not how we do a lot of regulations in other parts of the economy, right?

So, you know, if you take something like auto emissions regulations, honestly, if you take almost any environmental regulations, right, and often almost any consumer products and consumer safety regulation, the argument you get from industry is always, we don't know how to do this, you cannot require us to do something that we cannot do, right? And often the response has been, well, we don't believe you, so we're just going to require this, and then you're going to figure it out.

And in the context of, for example, auto emissions, where I think this has really been, and other environmental emissions, this really has worked time and time again, over many decades. Now, to be clear, the fact that it worked in one domain does not mean that it works in another domain. But I am curious, you know, Susan, why you think, or why sort of security folks are so confident that this is, in fact, impossible, right?

Susan Landau: Okay, so that's a very fair question, Alan. And there are two parts. I mean, the simple part, and I don't know enough, about military defense and weapons is to say, well, why don't we just test this particular weapon? Because we don't really believe it's going to have a catastrophic impact. The one time we did one of those, we were okay. But yeah.

Alan Rozenshtein: Yeah. As long as you don't literally light the atmosphere on fire, it's fine.

Susan Landau: Exactly. Exactly. But I think the, there's a two part answer to your question. The first is, although we've been trying damn hard for a while now, we still don't know how to build secure systems. And that's the real problem.

The second part is, okay, suppose we had diagnosed all the problems with Signaling System 7, and connecting the internet at phone switches and not properly authenticating, and so on and so forth, would we then get the whole problem fixed?

And the problem is that you move from the realm of science and technology and engineering to the realm of business. And I am not aware of the U.S. government sufficiently requiring security protections in various systems. I told a story in my Lawfare piece where I went to the FCC, Federal Communications Commission in 2011, and I had the weirdest half hour of my life. I'm in there and I'm saying, you have these CALEA switches and have you been threat modeling against them? And a half dozen, a dozen people in the room, and they're all looking at me like I'm nuts. They're asking me questions, they're not understanding what I'm saying, and I'm feeling like an incredible idiot. And in the last five minutes they say, oh my god, we never thought about that.

So there, the CALEA switch is supposed to allow wiretapping. It's a security breach in a switch. And these people hadn't thought about testing, testing the switches. Now I know that NSA tested a bunch of switches because they were buying them to use in defense systems and they had to test them. And what I got told by NSA was, every single switch they tested had a security flaw in it. And I said, and the rest were okay? And the person I was speaking with said, no, what I told you was everyone we tested had a flaw in it.

But the problem is that, one, building systems, complex systems, and the phone switching network is nothing if it's not a complex system. Building complex systems is bound to have security flaws. And if you look hard enough, you'll find them. That's problem one. Problem two is, fixing them costs money. It costs redesigning switches and systems. And for example, the U.K. has been trying to get Huawei stuff out of its phone network, for years now. And it still hasn't gotten there. It was supposed to be out over a year ago. It's not out. Regulation is great, but regulation doesn't work if you don't have sufficiently high fines to make sure the systems are secure. And that hasn't been the case with the phone networks. Now, of course, all my sources in the phone companies will die after that statement, but there it is.

But I, but those are the two things. One, it's technically really hard, and then two, when you find the problems, getting them fixed is very hard for different reasons.

Eugenia Lostri: So, Susan, let me follow up that. I don't think we're going to get wiretaps to stop, right? Like wiretaps are still going to continue happening. So, what does a better alternative to CALEA look like for you?

Susan Landau: I'll go back to what I said during the 2016 San Bernardino case, which is that law enforcement has to start using 21st century investigative techniques instead of trying to use 20th century investigative techniques.

So we had this period around 2000 to 2010, 2012, which was really a golden age for investigations. You arrest a guy, you pull the phone out of their pocket, you could search it without even getting a warrant. It's crazy, but there it was. But there was all this data on the phones and so on. And there wasn't encryption.

What we have now is probably something like 75 percent of cases have a digital component, whether it's simply that evidence is on the phone, evidence is on a desktop or a laptop. Now, it cannot be the case that state and local are all going to be experts in digital forensics, and so on. That's unreasonable. But the last time I looked at this, which was admittedly a few years ago, now they didn't have the capacity and there wasn't the capacity within the federal system, not to do the investigations, which they should not be doing, but helping to train and provide the technical tools for state and local. So it's one thing for New York or LA or Chicago or Boston to have forensic labs and other capabilities. But it's another thing for Springfield or Holyoke or Richmond to do so. And in those cases, the police do need help. So that's a large piece of it, learning how to use other tools.

Yes, I understand. And Alan will jump on me, but yes, I understand: when you're NSA, you're doing intelligence. When you're law enforcement, you need evidence that convicts without doubt. And those are different problems. Although we also have the case that in a very high percentage of cases people plea rather than actually go to court. So it's really rethinking how you do investigations in the digital age. And that's a combination, that I would say, Alan, I have your next research project for you.

Eugenia Lostri: I, on this point, let me just redirect anyone who's interested to listen to an amazing conversation I had with Joseph Cox, who wrote about Dark Wire and the AN0M operation, which I thought was an incredible example of innovative investigation by the FBI.

Susan Landau: Yeah, there's no question that there is some really great competence at the FBI.

Eugenia Lostri: Yes.

Susan Landau: We have seen that, but that competence needs to be much more widespread. Certainly, I had an experience in 2016 with somebody from the FBI who explained to me that it was really hard to deal with communications metadata when they came from different companies, because they were in different formats. And when I repeated that to my undergraduate computer scientists, and of course, in cyber law, they just started to giggle and I turned to the the graduate students in policy, and I said, did you get your answer about how hard it is? And they nodded their head.

Alan Rozenshtein: It's like 15 lines of Python code or something. This is not a complicated, you know.

Susan Landau: So that was one person, but a person who was actually heading an important office within the FBI, an operational office. And so, while I know that person has been replaced, the fact is that if you go down some levels, you still don't have the depth you need for the kinds of cases we're looking at.

Eugenia Lostri: So I want to look forward a little bit, and Alan already mentioned this a little bit, but I don't think we can actually get through an interview these days without talking about the incoming administration. So, you know, what do we know about the Trump administration stance on encryption. If anything will change and, you know, we know of likely upcoming changes in the FBI. What do we know? What can we expect? Can we do some guesswork here?

Alan Rozenshtein: Yeah, I'll be curious. I can start us off. I'll be curious though, Susan, cause I know you have a lot of, you know, a lot of contacts, I'll be curious what your sense is. I think it's very, very hard to predict actually here because, you know, on the one hand you expect Republicans to sort of be the kind of tough on crime party and all that sort of stuff, and the national security party.

But, you know, Trump is very suspicious of the quote unquote, deep state. So it's hard to know, you know, what he, or specifically his subordinates like, you know, Kash Patel or Tulsi Gabbard, right, the potentially incoming director of national intelligence, will say if their employees come and say, Hey, we have a real encryption problem.

So there's a lot of uncertainty there. You know, one big difference between Trump 2.0 and Trump 1.0 is that in this iteration, you have a lot more involvement from Silicon Valley in the administration itself, right? You have, Elon Musk is whispering in the ear. You have, you know, a lot of the Silicon Valley CEOs bending the knee. So I'll be curious to hear what they tell him, you know, I suspect that they will be I mean, I, they've been going dark skeptics for a long time. They've literally, I mean, in part because some of these are literally the same people that have been making the government's life difficult in this respect.

But it's also just extremely unpredictable, right? And so you could imagine some San Bernardino 2.0 thing happening, right? And then Trump decides actually he has to crush these companies that are making it difficult. So I just think you're entering into a huge period, frankly, of uncertainty more than anything else.

Susan Landau: I would certainly agree with the uncertainty. I think one thing that tips the balance slightly, but as Alan says, things change quickly. One thing that tips the balance slightly is that the news report said that some of the senior members of the Trump campaign were, their messages were listened into. That cannot make Donald Trump or his entourage happy.

Alan Rozenshtein: Unless he would like to be doing the listening in, right? I mean, that's always the question.

Susan Landau: In Silicon Valley, it's not just that they're very much opposed to controls on encryption. Their business model depends, many of those companies, on saying, we keep your information private. We don't share it, blah, blah, blah. Well, it's pretty hard to argue that and then say, oh, we don't actually care about encryption or end-to-end encryption, it's okay. But I think it's up for grabs both with the next FBI director and the one that will undoubtedly come sometime after him, but before four years are up.

Eugenia Lostri: The annual defense policy bill has $3 billion allocated to the rip-and-replace program, which seeks to remove Chinese made telecommunications technology from U.S. networks. And at a hearing last week, we had senators, we had experts indicating that this is a good start in defending against breaches like the Salt Typhoon breach that we've been talking about. So, if rip-and-replace is successfully carried out, does this change your calculus around encryption at all?

Susan Landau: No. No, for...

Eugenia Lostri: It's expected. Yes.

Susan Landau: For the reason I said originally, so telecommunications networks are hard. Electric power grid networks are hard, and they're more separate from the public than telecommunication networks. Any large piece of software is very hard to get fully correct. And we have determined adversaries. The Chinese have shown with this particular breach that their skill level, no surprise, has gone up. It's a large country with a lot of very smart people. No surprise in any of that. So no, it hasn't.

Alan Rozenshtein: Yeah I'll agree with Susan on this one, right? I mean, again I reserve the right to, to change my mind on any particular going dark issue, right, as the facts develop, but I don't think that if you're trying to figure out what is the marginal change in the underlying security infrastructure that like might get me to think one way or the other? I don't think getting the Chinese out of our systems is that change. I think it's a good thing, to be clear. I'm very supportive of it, right? I mean, I've spent the last year screaming about TikTok, right?

And so like, yes, if I think we should ban TikTok, I definitely don't think we should have Huawei switches right in the United States, or whatever the case may be. But for the same reasons that Susan just pointed out, even if you get the Chinese out of our systems in that respect, they're still in our systems in other respects, they're super, super skilled.And so if you're just thinking about the counterintelligence threat, there's no question that you want encryption sort of 24/7.

Susan Landau: I would have said 28/7

Alan Rozenshtein: 28/7, 28, 28/8.

Eugenia Lostri: Great. So, before we wrap up, closing arguments. You each have, you know, a minute or so. What do you want our listeners to leave this conversation with? Alan, you start. Susan can have the final word.

Alan Rozenshtein: I don't know. I mean, thanks, Susan, for being nice to me? Like, I don't have a, I don't have a good closing argument here, right? I mean, like, look I will just say I really try with these kinds of super technical questions where there are legitimate points, trade offs, and a lot of it is just very fact-specific.

I try to be a good Bayesian updater, right? And I try to be responsive. To reality as it develops and I'm okay making claims that then change as the facts develop, right? You know, I'm still proud of that paper and that argument that I made, and I think that it's fine that new information came to light that made me shift to a more encryption-friendly posture because of primarily the quiet that we saw, right? That's for me, again, the primary thing…

Susan Landau: Yeah, you’re just, me being beating you up

Alan Rozenshtein:That's just table stakes, Susan. I mean, a lot of it was the quiet that we saw, right? Which showed to me that the lawful hacking solution that I was skeptical of was more robust than I originally thought. And then plus seeing this CALEA disaster just as a very vibrant reminder of the kind of worst case scenario.

So, you know, I will say that that makes me comfortable. That the next time this issue comes up, I will be much more friendly to the encryption side, right? But again, I just, I really want to emphasize, you know, if there's a absolute catastrophe, right, that happens because of encryption, I will have to reconsider my priors and we'll just keep bouncing back and forth, like we do forever on all policy issues. At least that's how I, that's how I approach, and that is the least compelling argument, least compelling defense, but that's all I got.

Susan Landau: So I'm going to take you apart on nothing happens because of encryption. It's just hard to investigate because of encryption. But that aside, it makes me, one, very much want to clean up my act more than I have already on being more privacy-protective. But it really makes me argue for other people to do the same. All of us have a brother-in-law or a kid or an aunt who has a drug problem, has had an affair that the spouse doesn't, whatever it is, there is something going on that we'd want to keep private.

We have things that we would just as soon not share. We have business issues, or we're working for somebody important, or our kid's boyfriend is working for somebody important. There are all sorts of reasons why we should be using more privacy-protective, security-protective devices, and not sharing information to the extent that we do. And that, for me, is one of the takeaways, or maybe a main takeaway.

Eugenia Lostri: Great. Susan, Alan, thank you both for joining me and for being really engaging and good natured throughout this debate.

Alan Rozenshtein: It's easy when Susan's involved. Thank you.

Susan Landau: Oh, come on. Thank you, Alan.

Eugenia Lostri: The Lawfare Podcast is produced in cooperation with the Brookings Institution. You can get ad-free versions of this and other Lawfare podcasts by becoming a Lawfare material supporter through our website, lawfaremedia.org/support. You'll also get access to special events and other content available only to our supporters.

Please rate and review us wherever you get your podcasts. Look out for our other podcasts including Rational Security, Chatter, Allies, and the Aftermath, our latest Lawfare Presents podcast series on the government's response to January 6th. Check out our written work at lawfaremedia.org. The podcast is edited by Jen Patja, and your audio engineer this episode was Jay Venables of Goat Rodeo. Our theme song is from Alibi Music. As always, thank you for listening.

_-_flickr_-_the_central_intelligence_agency_(2).jpeg?sfvrsn=c1fa09a8_5)